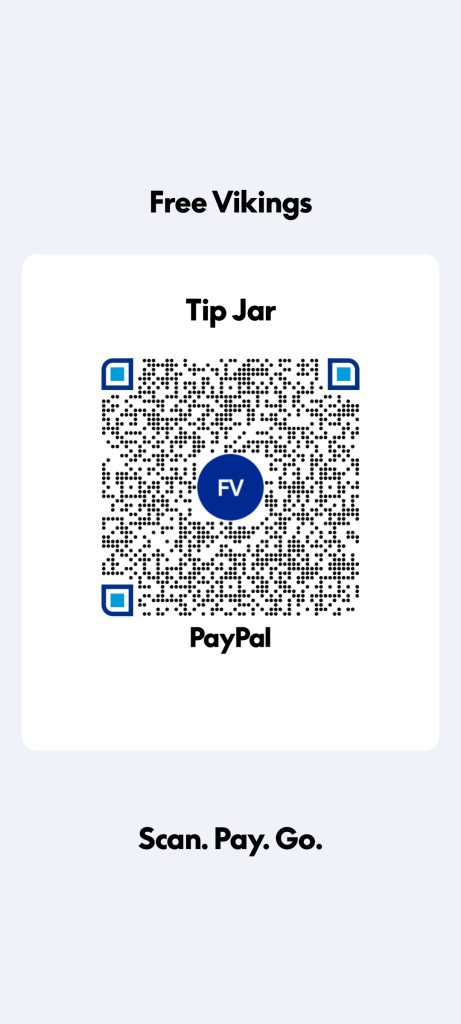

Let the wise present you with options.

Keep the world free. Tip the wise.

FreeVikings.com

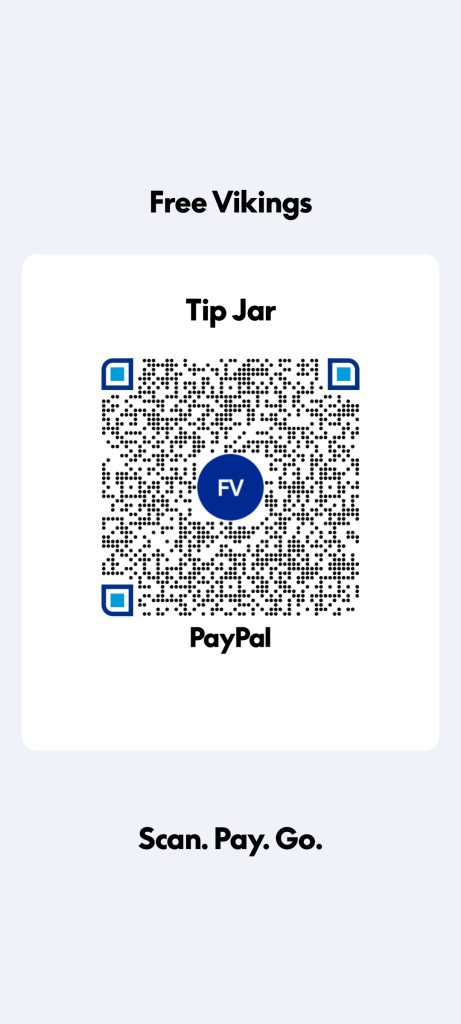

Let the wise present you with options.

Keep the world free. Tip the wise.

FreeVikings.com

The old Norse called slaves thralls (þræll), and thralls were the backbone of many a farm and household. Raids on Ireland, Britain, the Frankish lands, and even farther shores brought back thousands of captives—men for heavy toil, but women and girls especially prized. The Irish annals speak plain: in 821, the heathens struck Howth and “carried off a great booty of women into captivity.” Again and again, the chronicles note such hauls, for women fetched high silver in the markets of Dublin, Hedeby, or farther east along the Volga.

These foreign women—often Celtic from Ireland or Scotland, Slavic from the east, or others—served as cooks, milkmaids, weavers, and laborers. But many became concubines (frilles) to their masters. The Arab traveler Ibn Fadlan, beholding the Rus (Viking kin on the Volga), wrote of chieftains keeping scores of slave-girls for bed and trade, bedding them openly while others watched. In Laxdæla saga, the chieftain Höskuldr buys the Irish princess Melkorka at a slave market for three marks of silver—thrice the usual price—and takes her as concubine; she bears him a son who rises to fame.

Archaeology bears grim witness too: iron collars and shackles from trading towns, graves where decapitated women lie with wealthy men (sacrificed to follow in death), and bones showing hard lives far from home. DNA from Iceland tells the tale clearest—many founding mothers carry Gaelic blood, while the fathers are Norse, speaking of women brought across the sea, willing or (far more oft) unwilling.

The Perception wars are being outflanked by cool heads who know the futility of participating in the culture wars.

You teach calm and focused problem solving and you have far less problems. That begins with high quality platforms and tools.

South Korea’s post‑war transformation—from one of the world’s poorest nations after the Korean War (1950‑1953) to a high‑income economy with a per‑capita GDP north of $30 000—is often called the Miracle on the Han River. In the early 1960s average per‑capita income was only $80‑$100; the country then sustained almost 9 % annual growth for several decades, making its development story one of the most remarkable in modern history.

| Driver | What Happened | Why It Mattered |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Authoritarian, Development‑Focused Leadership | President Park Chung‑hee (1961‑1979) launched a series of Five‑Year Economic Development Plans beginning in 1962. The state set clear industrial targets, offered subsidies, low‑interest loans, and tax breaks, and imposed strict performance standards. | Created a “developmental state” that could allocate resources efficiently and push rapid structural change. |

| 2. Export‑Oriented Industrialisation | Early reliance on import substitution shifted in the 1960s to export‑led growth. The won was devalued, export incentives were introduced, and firms were steered toward labour‑intensive goods such as textiles and footwear. | Earned foreign exchange, raised competitiveness, and forced firms to meet international quality standards. |

| 3. Support for Chaebols | Large family‑owned conglomerates (Samsung, Hyundai, LG, etc.) received cheap credit, protection from foreign competition, and lucrative government contracts in exchange for investing in priority sectors. | Enabled economies of scale, accelerated industrialisation, and built globally competitive firms—though it also concentrated economic power. |

| 4. Massive Investment in Human Capital | The government expanded primary, secondary, and technical education, driving literacy to near‑universal levels and producing a skilled workforce. | Provided the talent pool needed for the shift from agriculture to manufacturing and later to high‑tech industries. |

| 5. Heavy‑Industry & Infrastructure Push | The 1970s “Heavy and Chemical Industry Drive” targeted steel, petrochemicals, machinery, shipbuilding, and electronics, while massive road, port, and power‑plant construction was financed largely through foreign loans. | Built the physical backbone for advanced manufacturing and export capacity. |

| 6. External Support & Geopolitics | • U.S. aid – over $119 bn (military + economic) <br>• Japan‑Korea normalization (1965) – $800 m in aid and technology transfer <br>• Remittances from Korean workers abroad (Vietnam, Middle East) <br>• Cold‑War alignment guaranteeing continued Western backing | Supplied essential capital, technology, and market access during the early stages of development. |

| Period | Main Focus | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s | Post‑war reconstruction, heavy reliance on U.S. aid | Modest growth (~4 % p.a.), widespread poverty |

| 1960s (1st–2nd Plans) | Light‑industry exports (textiles, footwear, wigs) | GDP growth 8‑10 %; exports rose from $55 m (1962) to >$100 bn by the 1990s |

| 1970s (3rd–4th Plans) | Heavy/chemical industries (steel, ships, automobiles) | Double‑digit growth; chaebols expanded dramatically |

| 1980s onward | High‑tech sectors (electronics, semiconductors) | OECD membership (1996); global leadership in technology |

While the model delivered spectacular economic gains, it also produced notable downsides:

Nonetheless, these trade‑offs laid the groundwork for today’s innovation‑driven, knowledge‑based economy.

South Korea’s experience illustrates how a coordinated mix of strong state direction, export orientation, human‑capital investment, and strategic external partnerships can propel a resource‑poor nation into the ranks of high‑income economies. The lesson for other developing countries is that focused government intervention—when paired with openness to global markets and a commitment to education—can accelerate catch‑up growth dramatically.

The Viking Cycle of Hamingja: Rise and Fall in the Sagas of the North. In the frozen fjords and storm-tossed seas of the Norse world, there is no desert—but there is the harsh edge: the wind-bitten coasts, the unforgiving waves, the thin soil of Norway and the wild Atlantic islands. Here, clans forged a force akin to asabiyyah, called hamingja—the inherited luck, the shared fortune of the kin, the unbreakable oath-bond that turned scattered households into dragon-prowed warbands capable of shaking kingdoms.

Hamingja is no fleeting chance. It is the clan’s vital fire: the collective courage, honor, and fate-weaving that binds brothers-in-arms. Strong hamingja brings victory, rich plunder, and lasting fame in the sagas. Weak hamingja brings nithing-status, exile, and the cold grave. Like Khaldun’s group feeling, it is born in hardship, peaks in conquest, and fades in luxury—only to be reborn in fresh clans from the margins.Being in Vik is like being in a Saga.- Freevikings.com